The Battle of Algiers (1965) proves to be an interesting and complex text to theoretically examine. I wish to discuss the construction of ‘truth’ stylistic and aesthetically represented in the film and the fluidity of ideologies signified when interacting with a contemporary audience. The film establishes a position as a factual depiction through the use of conventions which connote documentary realism. This utilises a ‘trust’ relationship between production and reception that the events depicted are physical reality, regardless of the presence of the camera. However, the of position ‘truth’ changes as signification varies with disparate spectatorship. While originally created in a strict ideological discourse, the film itself is not a practice of ideology but subjected to it. Therefore, when intercepted with a changing contemporary spectatorship the film’s ideological reception alters. Signification is thus a process of incompleteness, as the films discursive ideology is subject to and reinvented through the incorporation of divergent and capricious spectatorship.

Documentary Realism

November 19, 2006The premise of Pontecorvo’s film The Battle of Algiers (1965) was to create a film produced and shot within a ‘dictatorship of truth’; to reveal the ‘truth’ of a political situation that was heavily censored to the public (Solinas, 1973:66). A director who only made films ‘that need to be made’, Pontecorvo was encouraged to make a film that would definitely be banned in France when approached by Yacef Saadi (the actual military head of the FLN). Coming from a far-left political ideological position, Pontecorvo attempted to express the reality of the oppression of colonisation. In order to make the film as close to the illusion of the reality of the situation as possible, Pontecorvo chose to film in black and white, shoot on location and use local and unprofessional people as actors (Solinas, 1973:166). These conventions function to express an aesthetic of actuality and a position of factual authority to the film.

The stylistic aesthetic of The Battle of Algiers draws on convention exploited in documentary filmmaking. The documentary relies on an ontological contract between producer and audience that the film is a depiction of physical reality or ‘the raw material of actuality’ (Beattie, 2004:10). Structured by intratextual conventions that mediate viewer’s reception, the conventions of documentary filmmaking dogmatically insist that the depiction of the world is verifiable and accurate (Beattie, 2004:13). The interdependent relationship between representation and referent explored in documentary conventions functions as a sanction for the impression of authenticity, that putative reality is identical to profilmic reality. The authoritarian voice-over used throughout The Battle of Algiers explains this apposition. As the voice identifies characters and informs of political progression, the execution and language styles employed appears as though relaying information from mediums of physical actuality, such as police reports or newspaper articles. Although fictitiously used, by utilising media mediums that are culturally inscribed as tools for transmitting fact, the voice-over establishes the film as a representation of physical events that have taken place whether mediated through the camera or not.

The conventions of documentary filmmaking attempts to establish the profilmic events as a ‘truth’ of physical reality. The documentary discourse functions on the premise of a trust relationship between producers and audiences that events depicted are of physical reality. This ideology is limiting, as truth is represented as static and unchanging. However, the use of documentary inspired conventions employed in The Battle of Algiers does not ideologically limit its interpretation. Pontecorvo’s use of documentary conventions – grainy footage, hand held camera – utilises established contract of ‘truth’ between spectatorship and production, but as the film is an artistic interpretation rather than a factual report The Battle of Algeirs is not creatively limited to mere depicted reality. Documentary theory argues the style is rarely used for its own sake, as technical virtuosity or ornamentation, but to convey information. Pontecorvo uses this to his advantage; however this does not claim to a fictional realism as it relies on an imaginative relationship between viewer and the screen. Documentary conventions can be seen as restraining a film within a set of ideological and political discourses. Nichols argues that the rhetorical stance used to persuade and legitimise content expresses a ‘discourse of sobriety’(Nichols, 1994:119). Within this discourse the aesthetics of innovation become subservient to the documentary conventions (Beattie, 2004:17). As The Battle of Algiers is not a documentary, only merely employs some documentary techniques, the relationship between realism and artistic expression becomes fluid and interchangeable. Pontecorvo speaks from a liberated position of the freedom of post-structural free play of Avant-Garde filmmaking, but uses documentary conventions to establish authority for the benefit of a personal political agenda.

November 19, 2006

The lower image is a photograph of a women who was captured during the Algerian War of Independence. The image above is taken from the film. The aesthetics are noticeably similar. Pontecorvo chose to shot this film with the same photographic stylistic conventions of the media of the time, such as black and white as a opposed to colour, to establish the validity of his depiction.

Media Representation and ‘Truth”

November 19, 2006By exploiting the culturally conscribed meaning of conventions used in documentary filmmaking, The Battle of Algiersprovides a critique of the importance of media representation as a tool for transcribing hegemonic ideologies. During the Algierian war little, if any, uncensored information was easily accessible to the general pubic. During an interview Pontecorvo expressed the opinion that what information media represents, whether it is fact or not, is assumed to be ‘truth’. As a result Pontecorvo believed “an image is true to them which it resembles itself finished by the media” (Solinas, 1973:167). This cynicism implies that reality is only actual experienced when given virtuosity and authority of media representation. This argument, that an event is not an actual physical event until proven by the authorising of the media, fundamentally assumes that audiences are passive in the consumption of media interpretation. Pontecorvo is extremely critical of power given to the media as “the human eye is like a 32mm focal lens while the mass media audience is accustomed to seeing through the 200mm or 300mm lens” (Solinas, 1973:67). Ali, as a character of political insurrection, is most effectively experienced through the lens of the media. The grainy black and white footage imposes the impression of unrehearsed news reel. These conventions give the illusion that the event takes place regardless of the presence of a camera. The construction of the film as a cultural authority relies on the assumption that media representation functions as a depiction of ‘truth’. However, as the film is a rehearsed impression of reality and not spontaneous Pontecorvo explores how easily exploitable assumptions of ‘truth’ are. Hence, The Battle of Algiers provides a criticism to the authority culturally inscribed to the media as a convergence of ‘truth’.

While conventions of documentary realism affect the validation of the truth of Pontecorvo’s representation, the documentary is limited as a genre. The documentary discourse represents a static and self-contained version of history and knowledge. Documentary realism connotes the belief that physical reality, the unmediated image, can communicate its own meaning. This relationship is fundamentally flawed, as all information is mediated and merely an interpretation of physical reality. This is also expressed through the very medium of film, which is a process of manipulation through editing, lighting, and sound. The experience of the documentary as mediated through the filming process argues that realism is only achieved when physical reality is placed within a critical framework or incorporated within a discourse of representation (Polan, 1985:1). It has been established that The Battle of Algiers draws on conventions of documentary cinema in order to develop a relationship with the audience who perceive that the events are real. However, as the intertitle at the beginning states not one foot of the film is actual footage, the film is not limited by the presence of ‘real’ footage that would need to be accounted for and is given the freedom of unrestrained interpretation. The result of the combination of documentary convention and the freedom of fictional interpretation creates a free space for a representation of reality which is neither static nor unchanging. Nichols argues that aesthetic productivity rejects documentary reproduction (Nichols, 2004:5). This is not the same as rejecting knowledge or truth, but rejecting a static, self-contained representation of reality.

The role of the political film becomes more ambiguous and problematic when removed from a purely documentary realist position. Pontecorvo speaks with snide cynicism and contempt of the importance of media, particular filmic, in the development of ideology. Indeed, many comments made in regards to the importance of cinema are frequently contradictory. While Pontecorvo insists on the importance of cinema in the development of ideals, he also states that ‘cinema is not a revolution’. He asserts that cinema is a superficial medium which can only be read as ‘skin deep’, while simultaneously asserting cinema’s ability to revitalise ‘audience’s deaden responses’ (Solinas, 1973:190). These contradictions express the problematic position of a director of, what can be considered, an Avant-Garde political cinema, while being aware of the limitations of the medium. This confusion transcends into the film itself. The need for artistic expression is contaminated by the desire for the film to be taken as a depiction of ‘truth’. The use of street peasants as actors and a hand held camera creates virtuosity, while the dramatic use of editing to create identifiable characters, such as during the cafe bombing sequence, reflects artificiality and the ability for cinema to manipulate audiences. As the women plant concealed bombs, the camera focuses on the unaware victims. This sequence explores the political ambiguity of acts of terrorism. The camera exposes close shots of faces of innocence –teenagers dancing, babies eating ice creams and men sharing a joke. Juxtaposed with the hardened faces of the Algerian women and the image of a ticking clock, the scene is left with the helpless feeling of the moral ambiguity and confusion of the situation.

The treatment of the media within the narrative reflects the director’s cynicism. Media is represented as a culturally produced and maintained phenomenon, a powerful tool in persuasion with the ability to authorise the fidelity of a situation (Nichols, 1994:219). During a press conference Colonel Matthieu is posed the question of whether he believes France can hold its authority in Algeria. In response he comments that it depends on how well the media performs its ‘job’. Through acknowledging the cultural importance the media plays inscribing hegemonic ideologies, Pontecorvo adopts a critical perspective. However, the film then engages in a double entendre as the very discourse Pontecorvo is critical of, persuasive media, is the style adopted to establish the films authority.

The Role of Spectatorship

November 19, 2006The use of elements from two different conceptual discourses explores a new epistemological cinematic mode. Moving away from documentary realism as well as fictional escapism, The Battle of Algiersrepresents an ideational cinema; a cinema which deals in conceptualisation of the world (Polan, 1985:1). Polan argues that ideational cinema offers aplace for authentic politics between the world as showable (documentary) and the “idealism of poststructuralist free play” (Polan,1985:2). Reality disappears into a play of political signification. The final torture sequence explores the concept of ideational cinema. (Click on the YouTube link on the tool bar for a clip of this sequence). The use of aesthetic documentary conventions establishes the authority of images as actual events in physical reality. However, the removal of diegetic sound and the use of non-diegetic music, or perhaps the diegetic sound becomes subservient to the non-diegetic music, explores artistic expression. The effect is haunting. This sequence breaks with the discourse of the rest of the film. While the bulk of the film is depicted as events that are naturally occurring regardless of the camera’s presence, the torture sequences are removed from linear temporarlity. The affect of the music places the sequence as events that have already taken place, a memory of inhumane treatment. This sequence can hardly be expressed as purely documentary realism or fictional escapism; rather it presents a conceptualisation of reality.

The contemporality of The Battle of Algiersreflects not just on the structural elements of the film, but also on the importance of spectatorship and the nature of film apparatus. The physicality of watching film changes the nature of time. The spatial verisimilitude of the physical time of the length of the film versus the diegetic time and space removes the weight of the ‘real world’ (Friedberg, 1993:125). Thus, an essential element of spectatorship is temporal displacement, when the production and event are conflated at the moment of viewing (Friedberg, 1993:125). Freidberg argues that in this state of foreclosed ‘physic temporality’ history and the contemporality converge (Friedberg, 1993:132). In this space of collapsed temporality, the ideologies of the audience converge with the political discourse of the film. Thus, The Battle of Algiersis interpreted beyond the original intention. The significance of interpretation fundamentally relies on the epistimological position of the spectator.

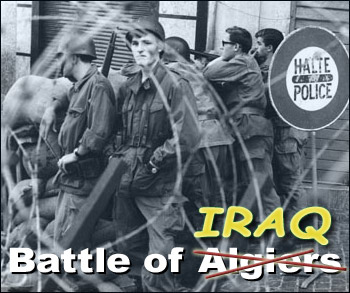

The meaning and impact of the film varies as the ideologies expressed are interchanged with the ideologies of the spectator. As part of a military training program The Battle of Algierswas screened for forty officers and experts as an example of urban Guerrilla warfare (Shatz, 2003:8). (See links on the tool bar for several articles which criticise and praise this use). The Pentagon considered this film as a realistic template to be applied to the Iraq war. The use of The Battle of Algiersin contemporary Military training indicates that meaning is directly related or engenders through spectatorship (Polan, 1985:10). The ideologically weighted events depicted in the film are neither understood through the event itself, nor through the form it is mediated, but through the articulation of the film through the spectator (Polan, 1985:14). The author of an opinion piece, Adam Shatz, was appalled that the Military interpretation of The Battle of Algiers failed to recognise the message of tenacity at the Algerian people who eventual claim their independence (Shatz, 2003:8). Although conventions and styles used within the film offer the site of meaning, the affect of the film relies on integrating with the non-specific codes of the audience. Thus to understand why The Battle of Algiers was screened as a military discourse is to comment on the position of the audience in relation to the signified discourse of the film. At the time of its inception, Pontecorvo was expressing a firm ideological stand point. Taken out of its original context the plurality of affects differs for each insertion of the film into disparate cultural practice of changing spectatorship. Hence, The Battle of Algiersdoes not express or practice an ideology, rather it exist as part of ideological practices, which alters with changing spectatorship (Polan, 1985:18). For Schatz, the film represents an example of the strength to overcome imperialistic forces. For Military experts it represents a case study of Guerrilla warfare and how Colonel Matthieu contains the situation. Neither interpretation is identical to Pontecorvo’s original premises. What differs is the incorporation of an audience’s ideological practice.

The meaning of the film changes as the signifiers employed take on new signification with varying audience. The original referents, what they re-represent, have become absent in contemporary viewing. The images are always understood within the constraints of the present tense. The referents are bought to “life in the present moment of apprehension, over and over” (Nichols, 1994:117). Drawing on the philosophy of the Postmodernist Baudrillard, contemporary spectatorship suffers from an over saturation of signs, as such signification has become fluid and free floating. No one fixed meaning can be attributed to signs in a contemporary context, indeed they are situated in the contradiction of signifying a multiplicity of ideas at the one time (Polan, 1985:21). For instance, the original political impact of The Battle of Algiers lay in the fact the film was actually made and permitted to be watched in some countries. The act of banning the film in France only gave more agency to the film’s importance. Similarly during the Algerian conflict underground screening of footage from Algeria was illegally shown in France. The importance of the screening was not the material shown, but the fact that these screenings took place at all (Dine, 1994:219). The political agency of The Battle of Algiers in contemporary context comes from the possible multitude of meanings which the film be interpreted. The film can represent an artistic interpretation of the horrors of colonialism, a contemporary understanding of the oppression of the West or a tactical piece of historical events. As the meaning changes, so to does the claim to ‘truth’. As the film can be interpreted in a variety of different ways, ‘truth’ becomes a fluid concept, completely dependable on context and personal interpretation.

The anxiety or crisis of the contemporary spectator in relation to historic representindicates a political dilemma in late capitalist society (Walkowitz, 1998:53). Walkowitz argues that the constant political restructuring of decolonised countries has created a political cynicism directed towards positions of authority (Walkowitz, 1998:53). For an audience arguably in an era characterised as Postmodern, a film that represents a historic realism undergoes a crisis of historical consciousness. Historical consciousness requires the spectator to recognise a paradoxical position; the moving images that are present refer to events that are past (Polan, 1985:117). This outlines problematic position for a Postmodern spectator when relating to historic representation; the anxiety to establish and identify ‘truth’ against propagandist media in the public sphere and distrust of dominant political culture (Freidberg, 1993:47).

The Battle of Algiersas a piece of historical representation further adds to the depth of signification in a contemporary context. From the foresight of a position further in history and an existing knowledge of thepropagandist role of media representation, audiences are aware of the dangers of colonialism, imperialist Western power and the need to claim independence. With this retrospect, signification is constructed from the present perspective but mediated through an understanding of past event (Nichols, 1994:119). Thus, signification for a contemporary audience is dependent on the way the spectator relates to history and to the film as a historical act. Through conscious engagement, the ideologies expressed in the film, whether interpreted as ‘truth’ or not, are evaluated against the personal discourse of the spectator. Thus, cinema not only acts as a signifier, but also as an open process, in which meaning is not encoded on the screen but through the spectator (30). As political cinema, indeed all cinema, is a constantly shifting relationship between referent and signs, dependent on the spectators own ideologies and cultural context, the depiction of events in history can not be seen as a static reality. Historical reality, and therefor historic fact, is thus an active process, constantly reassessed and accessed through reification of the relationship of the spectator within it (Polan, 1985:29).

The interpretation of The Battle of Algierschanges when intercepted with spectator ideologies. Therefore, although the film was construsted from an established political position, any ideologies expressed are subject to the non-specific conventions of the audience. The aesthetic conventions employed by Pontecorvo attempt to establish the film as a depiction of actual events. However, the concept of ‘truth’ varies as disparate audiences insert personal ideologies withdiffering signification. Therefore film, as a practice of ideology, is in a constant state of fluidity with mobile spectatorship.